Transforming Fear of COVID-19 Into Random Acts of Kindness

Preamble

The last time I purchased groceries was Monday, March 17th, just a few hours before the county of San Francisco entered into a Shelter-in-Place order. Stores had been short-stocked for days prior and the duality of densely-packed customers and panic buying behavior was psychologically damaging.

While my boomer parents recreationally visited Costco in suburban Minneapolis, I was preparing to avoid stores for as long as possible. Completely cognizant that the coronavirus has a 14-day incubation period, I worry that shopping in the recommended “2 week” cadence means that I’m constantly starting and re-starting the time clock on getting sick. My scientific-literacy strongly informed my assumption that grocery stores are a high-likelihood viral transmission vector. It’s the one and only place that most of us will still need to visit as the disease ravages on.

I’ve found the ethics of food delivery quite complicated. In “normal” times I’ve sometimes relied on Instacart or Amazon Fresh to outsource the task of shopping for groceries so that I can pursue leisure activities with the extra time. But this isn’t a normal time. Using a grocery delivery service during a pandemic is more like outsourcing my risk of contracting a serious disease to a presumably less privileged worker. That sits uncomfortably with me. Never mind that food items will be handled by someone with exponentially higher odds of community-transmitted sickness and that delivery services have experienced massive demand surges that have made reliability poor. Add in shortages of many items and the practical limitations of grocery delivery seem to bias towards a DIY approach.

After 29 days without stepping foot into a store and subsisting mostly on mismatched leftovers and a sack of produce that concerned friends insisted that I accept, it was time for a stock up. Having prepared a list of recipes to inform my list of items, I set off, fully prepared with my gloves, face covering, and washable tote (used in lieu of a purse so I could promptly give it a hot water wash when I returned home).

Inspiration

The day prior to my first shopping trip in a month, I tuned into an online lecture for Yale’s course on “The Science of Well-Being.” The class presents different material each week that pairs with “homework” assignments that complement the didactic components. This week, the take home portion involved writing a letter of gratitude and hand-delivering it. It paired with the homework from two-weeks prior, performing random acts of kindness.

Later that evening, I felt led to write letters to the people that would ring up my items at the 3 stores I planned to shop at: Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, and Target. Taking cues from Dr. Paula Whiteman’s heartwarming tweet about using the “cash back” feature to get $5 bills to distribute to store workers, I decided that I’d put a little bit of cash in each envelope, along with the notes.

These people aren’t making big bucks (national average in 2018 was $11.43 per hour) and if they’re lucky their employer is providing protective equipment or plexiglass partitions. Many are scared and all of them have to deal with impatient, anxious, and sometimes misbehaving shoppers. I decided that my trips to the store were the perfect opportunity to spread appreciation and support. In the best of times these workers receive little to no recognition or respect. Now, in the worst of times, the least I could do is rise up in the smallest way to spread kindness.

If Laurie Santos at Yale is right, my letters of gratitude might do just as much to make me feel good as the recipients who I’d leave an envelope with.

Execution

I used Peter Pauper Press stationery — cheerful for its “watercolor sunset” motif of colors. I kept each note to under 150 words, just enough to fill the page. I affixed a $10 bill with a piece of washi tape to the top of each letter so that it would be visible when the envelope flap was lifted. It was important to me that the envelope didn’t feel “scary” so making the cash visible upon opening felt sensible. I also wrote on the front of each envelope the following message:

“Thank you for serving customers at [STORE NAME]!”

Below is the transposed text of each letter.

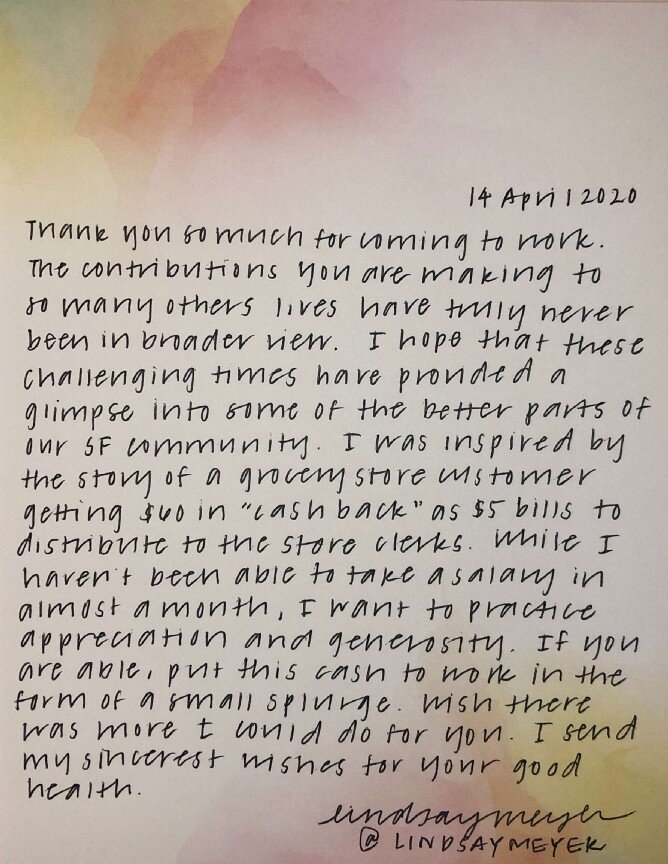

Note #1 | Thank you so much for coming to work. The contributions you are making to so many others lives have truly never been in broader view. I hope that these challenging times have provided a glimpse into some of the better parts of our SF community. I was inspired by the store of a groceery store customer getting $60 in “cash back” as $5 bills to distribute to the store clerks. While I haven’t been able to take a salary in almost a month, I want to practice appreciation and generosity. If you are able, put this cash to work in the form of a small splurge. Wish there was more I could do for you. I send my sincerest wishes for your good health.

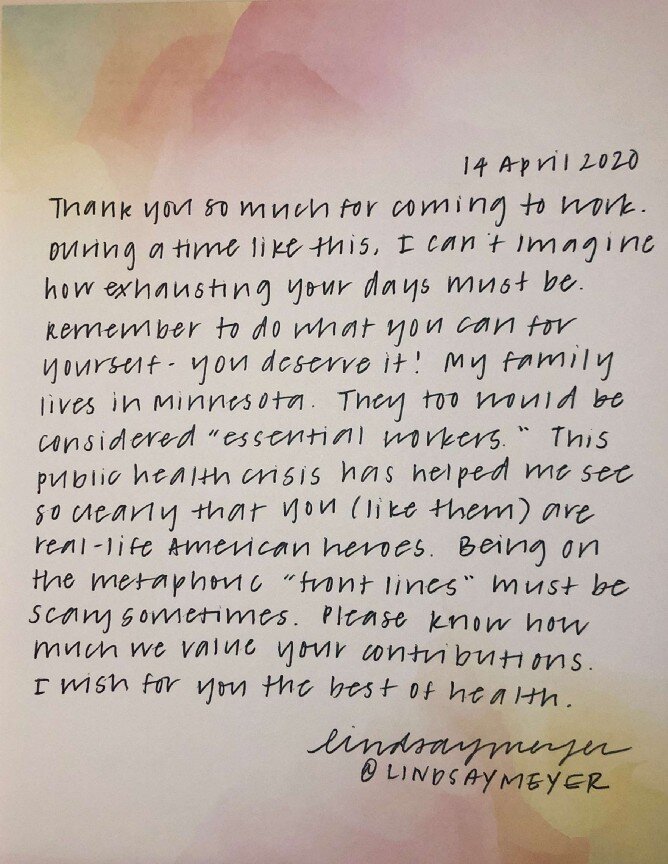

Note #2 | Thank you so much for coming to work. During a time like this, I can’t imagine how exhausting your days must be. Remember to do what you can for yourself — you deserve it! My family lives in Minnesota. They too would be considered “essentials workers.” This public health crisis has helped me see so clearly that you (like them) are real-life American heroes. Being on the metaphoric “front lines” must be scary sometimes. Please know how much we value your contributions. I wish for you the best of health.”

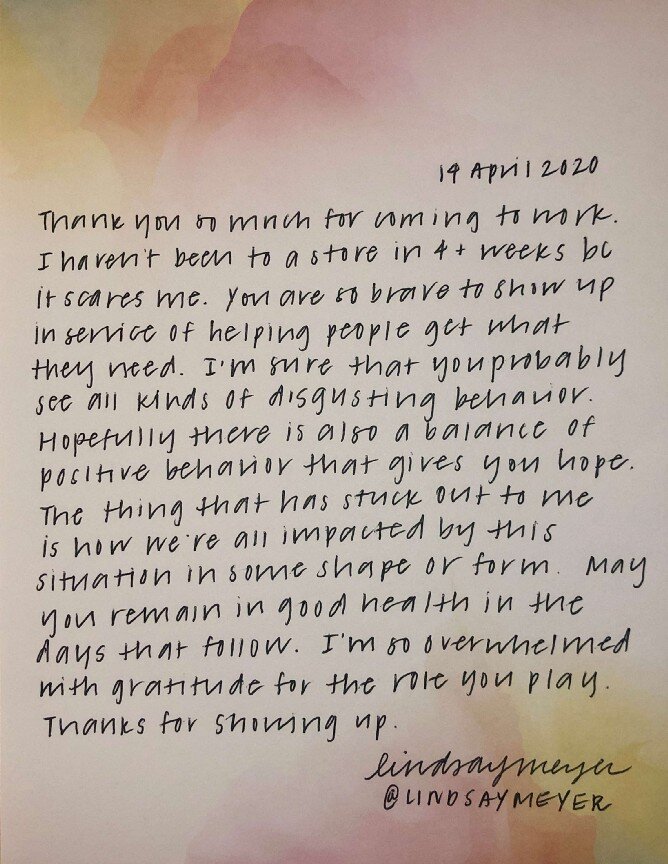

Note #3 | Thank you so much for coming to work. I haven’t been to a store in 4+ weeks because it scares me. You are so brave to show up in service of helping people get what they need. I’m sure that you probably see all kinds of disgusting behavior. Hopefully there is also a balance of positive behavior that gives you hope. The thing that has stuck out to me is how we’re all impacted by this situation in some shape or form. May you remain in good health in the days that follow. I’m so overwhelmed with gratitude for the role you play. Thanks for showing up.

Delivery

At each store, I had a somewhat limited exchange with the person checking me out. I used Apple Pay in every case and my items were bagged by the store workers. I had a strong moment of hesitation each time I dispensed the letters. I found that a natural point of exchange was the receipt handoff. In each instance, the person was quite surprised. I kept my words to a simple “this is for you” and walked off. I felt like a somewhat anonymous “good steward.” Knowing that at a future break or end of shift that these people would get a letter full of thanks and well-wishes for good health gave me great pride in being the type of person that sees the circumstances of others and finds a compassionate way to help create levity.

More than that, it transformed these previously-conceptualized “ scary” trips to presumed COVID hot spots into a mission for delivering lovingkindness.

The Movement

If you are inspired by this act, I encourage you to recreate or modify it to your liking. Here are some simple suggestions that you might find helpful:

Start your note by writing “Thank you so much for coming to work.”

Add a personal reference. Mentioning something that demonstrates appropriate empathy. Have your kids draw pictures. Write what you’re planning to do with the groceries you’re purchasing and how these meals are sustaining you.

Say what you’re grateful for or offer a sincere compliment.

Wish them good health. It’s nice to hear that others are acknowledging that there’s a high risk they could get sick from doing their job.

Consider adding cash to your note. Some stores do not allow their employees to receive tips, but if you put it in a sealed envelope with a note, it’s non-obvious and discreet.